We have to teach our kids that words have meaning.

Lois Bloom and Margaret Lahey co-developed a language model in 1978 that is still widely used by speech-language pathologists today. It separates language into three distinct, yet interconnected categories: form, content, and use1.

Form encompasses word order in a sentence, punctuation, and grammatical markers (morphology)

Content specifies the meaning of our message at the word, sentence, and conversation/paragraph level

Use dictates our intention when communicating. It’s what separates the perception of being informed versus persuaded

All three work together—change the order of words in a sentence, and you’ve not only changed the meaning but also the intention.

An early milestone that is simultaneously vital for cognitive and language development is intentionality. Our involuntary communication prior to three months old is for survival, but then we become intentional for the purpose of connection—think of a baby smiling, cooing, vocalizing, and giggling. Through these meaningful, reciprocal interactions, our brains begin categorizing words by sound (form), meaning (content), and intention (use).

In the book, What are Words, Really? , Alexi Lubomirski and Carlos Aponte have thematically highlighted intentionality by comparing and contrasting different uses of language.

Sometimes, our intention can be to share positive feelings like love and silliness,

and other times words are used to cause pain.

Most importantly, these words don’t only hurt other people, kids may unfortunately use words negatively towards themselves as well. Children with language-based learning disabilities often use negative self-talk and can exhibit extremely low self-esteem, both in and out of the classroom2; however, we know that neurotypical kids engage in self-deprecation and experience insecurities too.

Adults tend to defer towards narrative-led stories, like folktales and fables, to teach lessons and model life skills. These stories are indisputably valuable.

Finding a book whose central theme connects to a child’s experience can also provide catharsis3. Ultimately, kids want to connect with stories, whether the intention is to have fun, learn, or feel understood.

I have used What Are Words, Really? as a tool for kids to learn about the power of their words, or how to think about thinking—in clinical jargon we call that metacognition. It’s an important proactive strategy to teach at home that can lead to more robust peer interactions and meaningful friendships in any setting.

Curated for You:

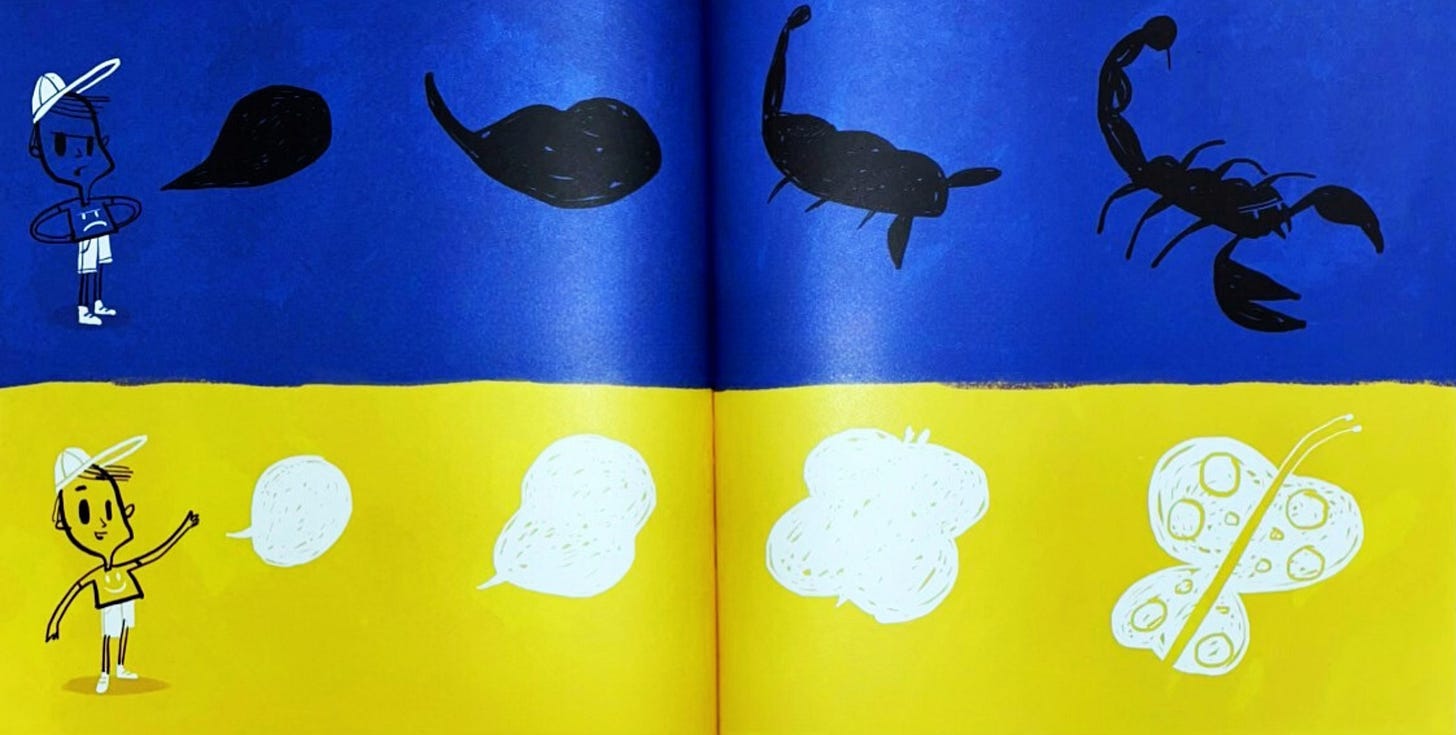

After you read the book, take out a piece of paper and a pen (or a white board and marker) and come up with two contrasting lists together—on one side of the page, there are “scorpion words” (and phrases) and on the other are “butterfly words.”

The goal is to create a visual that can be readily available at any moment, whether it’s hung on the fridge or in a bedroom. Providing validation when a kid is feeling sad and insecure can be important, but it’s not good for them to remain in that headspace for too long.

When you hear your child say, “I can’t do it!” or “I’m too stupid”:

Help them self-monitor their thoughts by playfully saying, “Oh no…do I hear scorpion words??”

Give them a second to process and see if they turn it around on their own

If they need help, then you reframe:

Playfully say something like, “We can’t have scorpions running around this room, this is a butterfly only zone!”

Point to the “butterfly word” side of the chart to cue them into choices of positive words and phrases to read out loud

If they cannot read yet on their own, you can give them two choices and see if that helps them connect to their sense of self

Keep in mind—books about words have multiple purposes. They can also teach metalinguistics, or the ability to think about and analyze language.

At this point The Book with No Pictures can be considered a modern classic, right? I’ve never met a kid who doesn’t enjoy reading this book over and over again. On top of being really fun and silly, Novak uses many different word forms and sound combinations that provide kids with opportunities for reading nonsense words. We are able to fluidly read nonsense words when we understand the relationship between letters and sounds (phonological awareness). When a child has difficulty breaking down nonsense words into syllables and/or individual sounds, it may be a sign of an underlying challenge with phonological awareness.

I love this book so much. Kobi Yamada layers themes of change, self-expression, communication, and connection that will bring new meaning to your child as they grow and develop. Not to mention, the illustrations are unique and beautiful. The book can guide a child’s understanding of intention behind communication—not only what is your idea, but how are your ideas going to impact the world around you?

Do you love learning random facts? Do your kids? Do you like discussing them as a family? Well, have I found the perfect book for you!

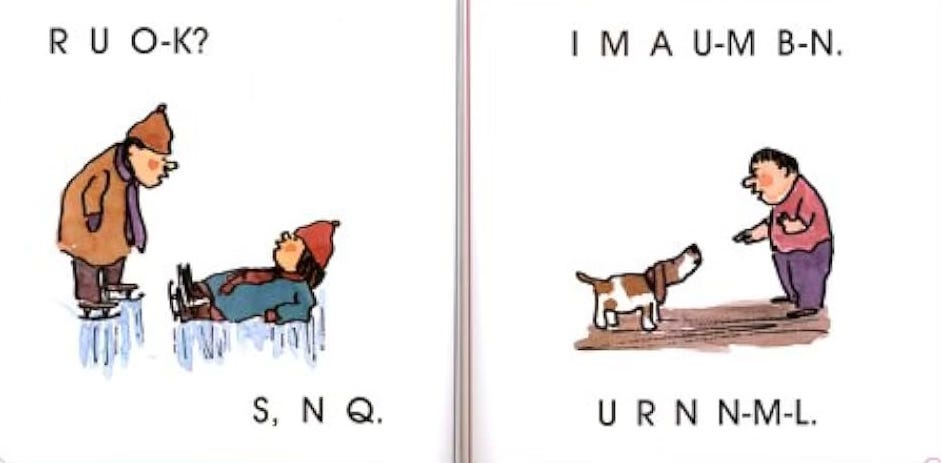

Everything that William Steig has written should be an immediate Add to Cart. I’ve had CDB! on my bookshelf for many years, and the kids really get a kick out of it. Each page showcases how letters, and the sounds they make, can also be words.

Again, books like this are a great way for kids to playfully learn sound-letter correspondence and the relationship between the “content” and “form” of language.

If you’re looking for other books, peruse no further than The Curated Library.

You can find my favorite books to read with kids, the best mysteries for all ages, books that teach kindness and empathy and all of my other curations on Bookshop.org

https://archive.org/details/languagedisorder0000lahe

https://childmind.org/article/how-to-help-kids-with-a-learning-disorder-build-confidence/

Color Monster is a great example