A few weeks ago I spoke with

about early language learning. We discussed a few pertinent topics that tie in nicely with today’s newsletter. If you haven’t gotten a chance to read our conversation yet, you can find it here.Which came first, the infographics or the interest?

Oversimplified information posited as expertise is pervasive on social media.

Admittedly, since starting this newsletter journey, I’ve become very sensitive to how clinical information is shared on the internet. I work really hard to break down information rationally and clearly, so that I don’t scare anyone, sensationalize possible language delays, or overemphasize red flags, because I recognize how distressing it can be to read something online and immediately personalize it to your family’s experience.

Speech-language pathology can be a really interesting career, in the sense that some people have absolutely no idea what I do for a living. I understand why it’s confusing. Colloquially I’m referred to as a “speech therapist” or a “speech teacher,” but it’s actually kind of a misnomer. I’m rarely working on just “speech,” even though I’m supporting people to speak every day. My focus is on language, hence why I am always sharing language-focused strategies and ideas.

A significant part of my undergrad and graduate education focused on learning about typical development, so that I could later identify deviations from the evidenced-backed normative data. I then worked in a school that utilized a developmental model based on Piaget’s theory of cognitive development for a little over a decade, and I still use DIRFloortime® as the foundation of my work to this day. My whole career is seemingly flooded with milestones, so much so that it’s sometimes hard to turn that part of my brain off; therefore, I can confidently say, the developmental language milestones mentioned in those infographics aren’t as important as they’re projected in totality.

Developmental milestones are necessary benchmarks for receiving a diagnosis and appropriate services.

They’re not helpful for every day parenting.

Milestones aren’t grades, or awards, or any kind of achievement. They’re stepping stones along our developmental trajectory.

Our brains change throughout our lives thanks to neuroplasticity and neural pruning; we are constantly creating and updating streamlined pathways to send the quickest, most efficient signals to and from the rest of our bodies. There is so much research out there, and frankly bad advice, claiming limitations around our ability to learn by a certain time1. Wrong! Early intervention is absolutely best practice, but that does not mean that beyond three years old a non-speaking child won’t ever talk or that a fifth grader will never learn how to read.

Don’t base your child’s future on the pacing of their milestones. That’s not how learning works.

We all have our own range of “normal”

In the early 20th Century, a Russian-Jewish scholar named Lev Vygotsky2 created a new model of child development named sociocultural theory. As a scholar of eight different languages, he was able to procure a breadth of knowledge about psychological theories from various parts of the world, most of which at the time focused on the self (remember, this was the era of Freud’s psychoanalysis).

Instead, Vygotsky saw development as something that occurred outside the self as a member of our collective society3. He theorized that human development is impacted by four key components:

genetics

world history and its events

our personal experiences in childhood and adulthood

how we master a single task

This last point—mastery of a task—takes us to his most well known concept, the zone of proximal development.

What is The Zone of Proximal Development?

In the book titled Childrens’ Learning in the Zone of Proximal Development, the following explanation is outlined:

The zone of proximal development involves the joint consciousness of the participants, where two or more minds are collaborating on solving a problem. A corollary of this notion of intersubjectivity is that the participants do not have the same definition of the task or of the problem to be solved. Through their interaction, the child’s notion of what is to be done goes beyond itself, with the adult’s support, and comes to approximate in some degree that of the more expert adult.

Second, both of the participants play an important role in using the zone of proximal development, even in situations that are not directly conceived of as instructional by the participants. The child provides skills that are already developing and interests in particular domains and participates with adults and organizing and direction and pace of interaction in the zone of proximal development. The adult has particular responsibility for segmenting the task into manageable subgoals and for altering the child’s definition of the task to make it increasingly compatible with expert performance. Although intervention and assessment can be finely tuned to match the growing edge of the child’s competence, there are circumstances in which what the child is encouraged or allowed to do does not does not fit the child’s immediate potential growth.

Third, interaction in the zone of proximal development is organized into a dynamic functional system oriented toward the child’s future skills and knowledge. The functional system of adult-child participation in problem solving is organized by the task definitions, promoted activities, and hard and soft technologies available through culture.4

Thinking and communicating develops from the back-and-forth social interactions we have with other people, not just from our individual experiences. In order to learn new information and solve problems, we need experienced, competent members of our community to nurture and teach us. That information is collected from their own experiences and knowledge of our world’s history.

Keeping the zone of proximal development in mind, we are always aiming to:

Meet the child where they are, or be aware of what they currently know independently

Challenge their thinking just beyond their current level of knowledge. In the DIRFloortime® provider community, we refer to this as a “just right challenge”

Provide scaffolding, aka little clues, that allows the child to experience discovering something new with enough freedom to feel that they’ve figured it out (mostly) on their own

Instead of seeing our lives as a series of milestones, let’s frame our experiences as an ever-expanding chain of highly motivating and meaningful learning moments. It’s our successes and our failures; it’s about learning the values of resilience, kindness, and gratitude. Don’t get caught up with all of life’s prescribed checklists, give your child the opportunity to create their own.

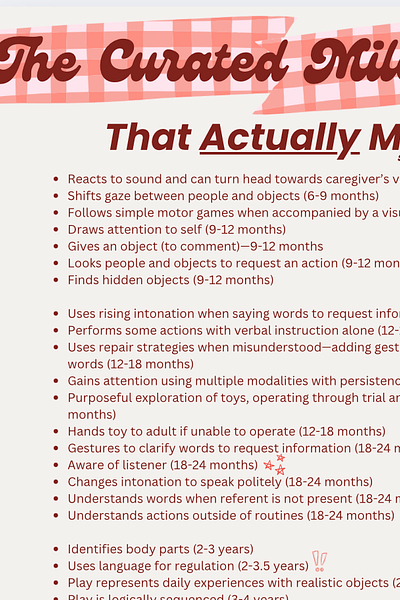

THAT BEING SAID—If by chance you do need a milestone checklist because you are worried about language and/or developmental delays, here is a complete guide of milestones that I think actually matter.

Your readership means so much to me. As a big thank you for the support, I have made this handout free to download.

Should you have any follow up questions as a result, consider becoming a paid subscriber to gain access to future workshops and opportunities to consult with me directly about your child’s development.

If I received money for every time a parent reported someone saying that their kid would never speak/learn/have a life/be successful, I’d be writing this from a Nancy Meyers-inspired deck eating lobster salad from Loaves and Fishes

Lev Vygotsky graduated from Moscow University with a degree in law, one of a 3% quota of Jewish students allowed admission at random, while finishing his studies at the Shaniavsky’s Peoples University. He had to attend an alternative university in order to study philosophy, the arts, literature, and psychology, because Jewish students at the time were limited to certain areas of study, like medicine and law, that were deemed less “prestigious.” It was there that a group of professors, who were considered enemies of the government, introduced him to the work of Jean Piaget and other developmental psychologists. He graduated in 1917, just before the Bolshevik Revolution.

Berk, L. E., & Winsler, A. (2002b). Scaffolding children’s learning: Vygotsky and early childhood education. National Association for the Education of Young Children.

I mean, he was a Marxist after all.

Rogoff, B., & Wertsch, J. V. (1984). Children’s learning in the “Zone of proximal development.” Jossey-Bass.

This is perfectly timed. I have a four-year-old and an almost eleven-month-old, and it's been challenging to avoid comparing their development, despite knowing they're unique individuals. The checklist is truly helpful. Thank you!