Somehow I walked 19,866 steps on Saturday.

I tend to take a familiar loop most weekend mornings through my favorite picturesque downtown neighborhoods. I love picking up coffee and a baked good, so these are often my anchoring landmarks for a stroll. If you know me, you know that I love collecting new bakeries and coffee shops for my detailed spreadsheet, but I also enjoy re-visiting my favorites over and over again. I like seeing familiar faces behind the counters; it reinforces the close feeling of community many believe is non-existent in a city like New York.

When I’m not taking my preferred route, which at this point is almost reflexive, errands will take me on side streets and alternate paths. I relish in the opportunity to admire the various architecture styles and to be inspired by what people are wearing as I wait to cross the street. Then there are the signs—so many signs. Signs detailing famous people who lived in now historic homes. Beautiful neon that isn’t produced quite the same anymore. Plaques identifying salient moments in the city’s history. One of my best friends stops at every one of these signs and commits them to memory—this is one of the reasons why we’re best friends.

Jane Jacobs talks about the inherent value of sidewalks in her book titled The Death and Life of Great American Cities, for which the Rockefeller Foundation provided a grant to research, write, and publish in 19611. In fact, there are three whole chapters just about sidewalks, chapter 4 in particular being titled The uses of sidewalks: assimilating children. I pulled the following excerpt to showcase how relevant I continue to find her research; learning how to relate and communicate with others is dependent on being able to form trusting, meaningful relationships:

The people of cities who have other jobs and duties, and who lack too, the training needed, cannot volunteer as teachers or registered nurses or librarians or museum guards or social workers. But at least they can, and on lively diversified sidewalks they do, supervise the incidental play of children and assimilate the children into city society. They do it in the course of carrying on their other pursuits.

[City p]lanners do not seem to realize how high a ratio of adults is needed to rear children at incidental play. Nor do they seem to understand that spaces and equipment do not rear children. These can be useful adjuncts, but only people rear children and assimilate them into civilized society.

It is folly to build cities in a way that wastes this normal, casual manpower for child rearing and either leaves this essential job too much undone—with terrible consequences—or makes it necessary to hire substitutes. The myth that playgrounds and grass and hired guards or supervisors are innately wholesome for children and that city streets, filled with ordinary people, are innately evil for children, boils down to a deep contempt for ordinary people.

In real life, only from the ordinary adults of the city sidewalks do children learn—if they learn at all—the first fundamental of successful city life: People must take a modicum of public responsibility for each other even if they have no ties to each other. This is a lesson nobody learns by being told. It is learned from the experience of having other people without ties of kinship or close friendship or formal responsibility to you take a modicum of public responsibility for you. When Mr. Lacey, the locksmith, bawls out one of my sons for running into the street, and then later reports the transgression to my husband as he passes the locksmith shop, my son gets more than an overt lesson in safety and obedience. He also gets, indirectly, the lesson that Mr. Lacey, with whom we have no ties other than street propinquity, feels responsible for him to a degree. (Jacobs, p. 81-82)2

The uses of sidewalks: learning

Just like the grocery store, another valuable and overlooked learning environment is your very own neighborhood sidewalk. Today we’re focusing on the important language-based life skills children learn going on a walk.

Identify Meaningful Landmarks

Regardless of where you live, important landmarks exist all around you. They act as consistent visual anchors and add to the fabric of a community’s culture. In addition to the historic homes, old buildings, and statues in our neighborhoods, kids will attach meaning to the simplest landmarks—think about a beautiful tree in your neighbor’s front yard, a cat you always see napping in a front window, or even a Little Free Library.

As you walk around your neighborhood or along the main street of your town, you can begin to identify the landmarks that are meaningful to your family. This is a prime opportunity to follow your child’s lead. When they notice something interesting, validate this discovery and make it a notable landmark on your journey.

Identifying these objects and places helps broaden children’s background knowledge of shapes, raw materials, historical events, and physical properties of nature.

You can also support their inferencing skills when they inevitably ask hypothetical questions like, “what happens if that tree falls over?” and “why is that house pink?” Maybe you even draw your own map together, adding landmarks over time. You will be pleasantly surprised to see all of the details kids pick up on when they are clued in to the world around them.

Become a Regular

As Jacobs mentions in the quote above, it’s important to form relationships with people outside of your family and inner circle. Communicating with less familiar people, strangers in particular, is one type of discourse with its own set of rules. We (hopefully!) change our tone of voice, our speech rate, and the formation of our sentences in order to sound polite when talking to less familiar people.

Over time as we get to know these people better, our relationship alters the way we communicate—we create a familiar script made up of small talk, repetitive ideas are shared that can become “inside jokes,” and generally our communication feels increasingly relaxed and casual. This distinction is very important for kids to learn, and it can only be gained by observing a trusted adult’s modeling.

When you become a regular at a store or restaurant, you are also teaching your kids respect, gratitude, and courtesy as you are:

Greeting a person and asking someone how they are doing that day

Saying “please” and “thank you” genuinely and kindly

Finding commonalities and learning about people’s lives outside of their job

Providing guidance and support when appropriate

Calmly repairing communication breakdowns and problem solving mishaps

Offering help when needed

Setting professional boundaries

Use a Map

Being able to orient to our environment enables our ability to read and use maps. This can be particularly challenging for neurodivergent kids who often experience decreased body awareness and may need sensory integration support to process how their body moves in space. Spatial (direction) and temporal (sequences of time) vocabulary words are embedded in the language of mapping, a functional way we all follow directions outside of a classroom.

Let’s take this direction, for example:

After you pass 10th street as you’re walking up Greenwich Avenue, you’re going to see the bakery on the right side of the street. It’s the third store in the middle of the block3.

After you pass 10th Street—tells us “when;” helps us to sequence events correctly

Up Greenwich Avenue—tells us which direction to go in (spatial concept), but obviously we’re not really going up we’re going forward. Introducing an idea in this manner models cognitive flexibility and the concept that words can have multiple meanings.

Right side of the street—another spatial concept, this time differentiating one side of our body from the other

Third store in the middle of the block—requires sequencing and spatial knowledge simultaneously

As you take a walk, narrate these types of directions out loud to your kids while referencing a map, whether it’s on your phone or a paper copy, so that they can begin to familiarize themselves with these ideas in the moment. It’s especially helpful for when you get lost. Can they recall which turn you took that might have been wrong? Maybe you can problem solve together by using the map.

Read All of the Signs

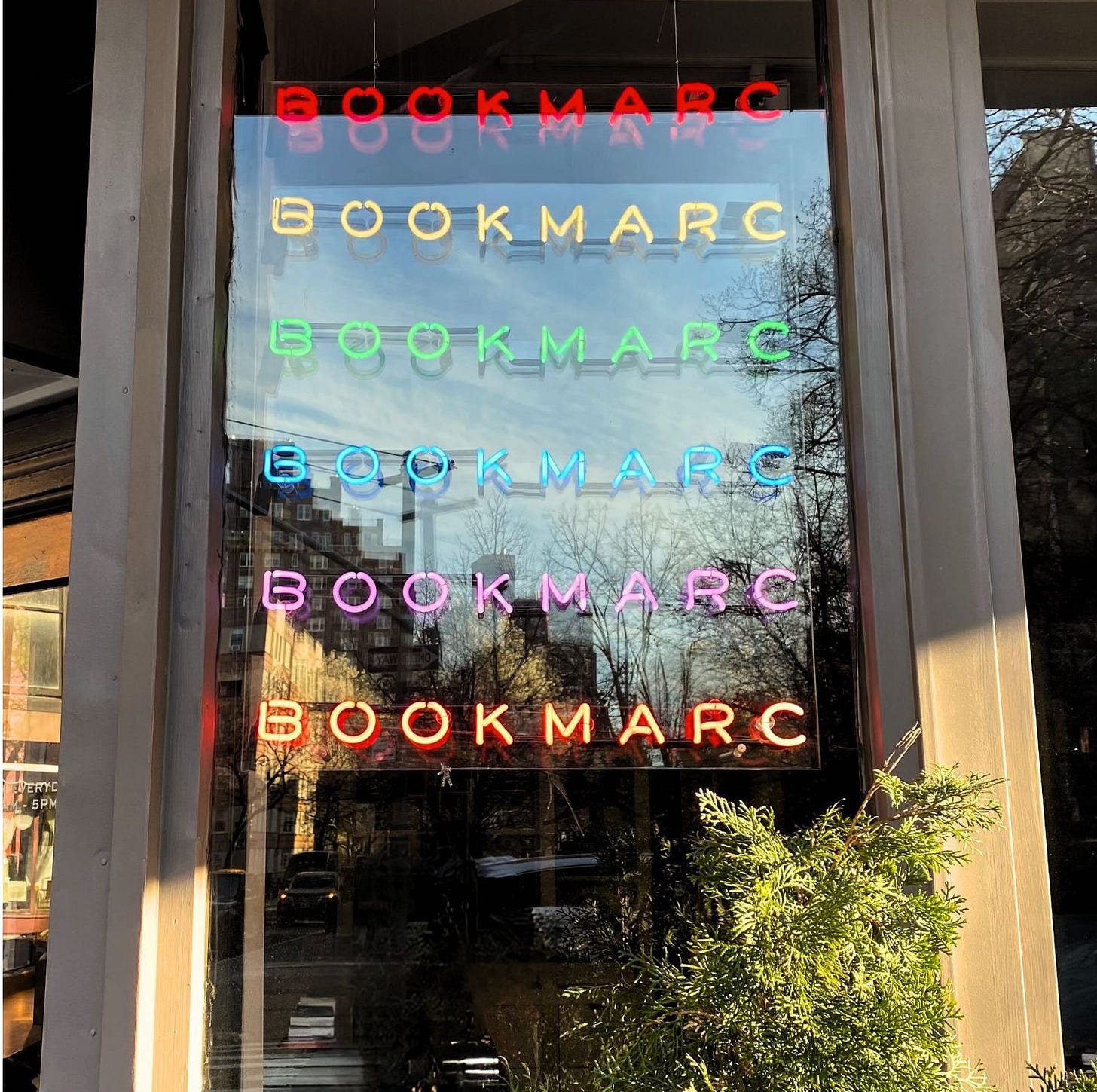

If you’re looking for free reading material, all you have to do is walk around your neighborhood and read the signs. Kids are unknowingly exposed to so many new language forms while looking up at the writing on the walls.

Signs model a variety of spelling and sentence patterns in addition to presenting humorous and creative ideas in various fonts and symbol systems.

Street signs can be comprised of simple sound combinations that correspond to letters in a word (i.e. phonics)—from simple ones like Lane to more complex words like Boulevard. This can also be an easy vocabulary lesson and opportunity to compare/contrast

Traffic signs use symbols to represent universal ideas and help build community safety awareness

Promotional signs—buy 1, get 1 free and 2 for 1—can build background knowledge for learning about fractions and percentages in future math classes

Business names on signs are often one of our first exposures to figurative language forms, like alliteration, puns, onomatopoeia, and personification (Mr. Softee anyone?). They also provide the opportunity to discuss complicated literary devices, like irony and metaphor. These different symbolic uses of language are helpful in connecting with others during conversation, as well as when we’re reading and writing in school.

Let’s take the sign below, for example—

It says, “Spring Scaffolding: Reaching New Heights”

Looking up, two things come to mind.4 First, the brand’s tagline contains a pun (scaffolding—heights), but the other is the metaphor a cherry tree blooming around the scaffolding reveals. Visually it presents the possibility of Spring helping lift the building to reach new heights in addition to the white beamed scaffolding. Spring is often symbolic of newness and rebirth, so in this instance it’s metaphorically acting as an agent of change for this renovation.5

When I saw this from across the street I immediately chuckled and walked over to take this picture. I would imagine that if a child were next to me in that moment they may ask me why I laughed, providing an opportunity to help support [again, no pun intended] their metalinguistic knowledge. In doing so, I am explaining the humor behind the situation, or even ask a reflective question like, “why do you think this was funny to me?” while pointing up at the tree.

Choose Your Own Adventure

What happens when we can take time out of our day to be more adventurous and open-ended? I used to love reading Choose Your Own Adventure books, because the possibility of choice in storytelling was exciting and different. Taking a walk can be the perfect context to leave actions up to chance and involve multiple family members in decision making.

You can decide if you want to reach a destination or just wander

You can use a map or go from memory

You can take turns deciding which street to turn down when you reach a stop sign, cross walk, or red light (I suggest picking an order and repetitively rotating through)

You can set a timer and change course when the timer goes off

You can try to reach a familiar landmark by purposefully avoiding the streets you usually take

Maybe one of your kids even comes up with an original rule, and it eventually becomes a part of your routine and family lore. The choices are endless and the rules are your own.

Find Joy in the Gaps of Silence

Taking a walk can be a great opportunity to foster a continuous flow of engaging conversation where you’re discussing multiple topics and telling stories. It can also be a great time to just enjoy being together in silence, which is also an important conversation skill.

Frankly, kids need to learn when to stop talking. They can get very excited about sharing ideas or making personal connections, especially if they are neurodivergent, and may not always innately recognize the nuance of conversational pacing. When you’re walking next to someone, you mostly rely on your auditory system to listen out for a break in conversation instead of being able to see when the other person or people have paused. In this way, walks are a natural context to practice reciprocity.

Simultaneously, kids should be learning how to feel comfortable when a conversation naturally drops off. They don’t always need to keep it going! In fact, it can be really grating for certain people when their conversation partner never stops talking. Learning that sometimes we can just walk together and take in the world around us—focusing on moving our bodies, and the warm breeze, and the beautiful sunset— and then talk about what we saw when we get to our destination is the goal.

Its intention was to continue her fight against Robert Moses and other developers from ruining major cities, including New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia amongst others.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, 1961.

Yes, I am talking about Mah-Ze-Dar

You may notice more, and I’d love to hear them in the comments

Don’t mean to get so deep, but here we are

As always, you’ve added so much depth and opportunity to what parents already have access to. I absolutely loved this post!

I LOVE THIS!!