The following content may contain affiliate links. When you click and shop the links, I earn qualifying commission.

The beginning of the year is a time for us to feel our most efficient. We’re list makers with goals and sweet little treats to reward ourselves for getting a few goals knocked off our to-do lists (it’s me, hi. i’m the problem. it’s me). We also might be a little delusional in thinking that we’re super multitaskers who can take on a much larger workload than is actually possible, because guess what—our brains can’t actually multi-task.

When attempting to “multitask,” the brain, “rapidly switches from meeting the demands of one task to meeting the demands of another.”1 Your brain may be able to do multiple tasks simultaneously, but at least one of them is probably rote and automatic like driving, unloading the dishwasher, or sorting. That’s not to say you need to lock yourself in a sensory deprivation chamber or shut out all human interaction to be efficient. Our brains actually benefit from social interaction to increase efficiency, similar to exercising, because sensory input and interacting with others is regulating and helps us focus for longer periods of time.

Most of the skills we need to manage our time efficiently are activated in the pre-frontal cortex, the part of our brain that sits right behind our forehead. This region of our brain also helps us with executive functioning in addition to conscious thought, emotional processing, critical thinking, and perspective taking. Our frontal lobes don’t fully develop until 25 years old, which is why time management is a huge part of our school experiences. Part of our jobs as teachers is to model and frankly, coach students in devoting a certain amount of time to tasks. I attribute my time management skills in part to my fourth grade teacher Mrs. Spier, who was not only one of my favorite but also one of my most supportive teachers. She started off our school year assigning homework that took me and my classmates around 4 hours nightly; it was through her unique combination of encouragement, patience, and tenacity that I figured out how to get my work done in an hour and a half without sacrificing the quality of my efforts.

Over time and with repetition, neurotypical individuals will be able to pick up on patterns and rely on their internal clock to manage their time. But imagine not having a reliable internal clock, or having trouble with sequencing, or having difficulty keeping track of your personal items because your brain inconsistently processes that an object exists when out of sight, or not being able to prioritize because you can’t fully comprehend what “important” means, impacting your ability to decide which tasks are “important” and “unimportant/less important.” That doesn’t even take into account that this is all coming from your POV, and we must factor in other people and their opinions of what is “important/less important.” With all of that in mind, you can imagine why time management is gonna be pretty hard for young children in the early stages of development and neurodiverse individuals.

As typically developing adults, we usually manage our time through strategies like:

Calendars (physical and online cloud-based systems)

Wearing a watch or keeping track of time on our phones

Digital reminders (alarms, calendar alerts)

Analog reminders (sticky notes and notepads)

Hiring a personal assistant

Conversing with a partner/spouse, family member, friend, and/or coworker

At home and out in the community, we are constantly modeling the use of these supports subliminally for children. Some may naturally want to emulate the adults or older kids in their lives that they look up to by imitating these strategies. However, others may have trouble writing, reading, or being able to hold onto information in the moment as they move through a task (i.e. working memory). In that case, some other strategies may be more helpful or could supplement these traditional ideas.

Assigning a dedicated, central space for reminders so that your child has a predictable place to retrieve important information, like a wall in your kitchen or by the door. You can even give that place a special name, like the Calendar Corner or whatever would be fun and motivating to your family

Using pictures on a schedule instead of writing words on a calendar or list

Using a daily calendar or weekly calendar instead of a full month calendar

Talking a plan through in small segments and deciding the order of operations together

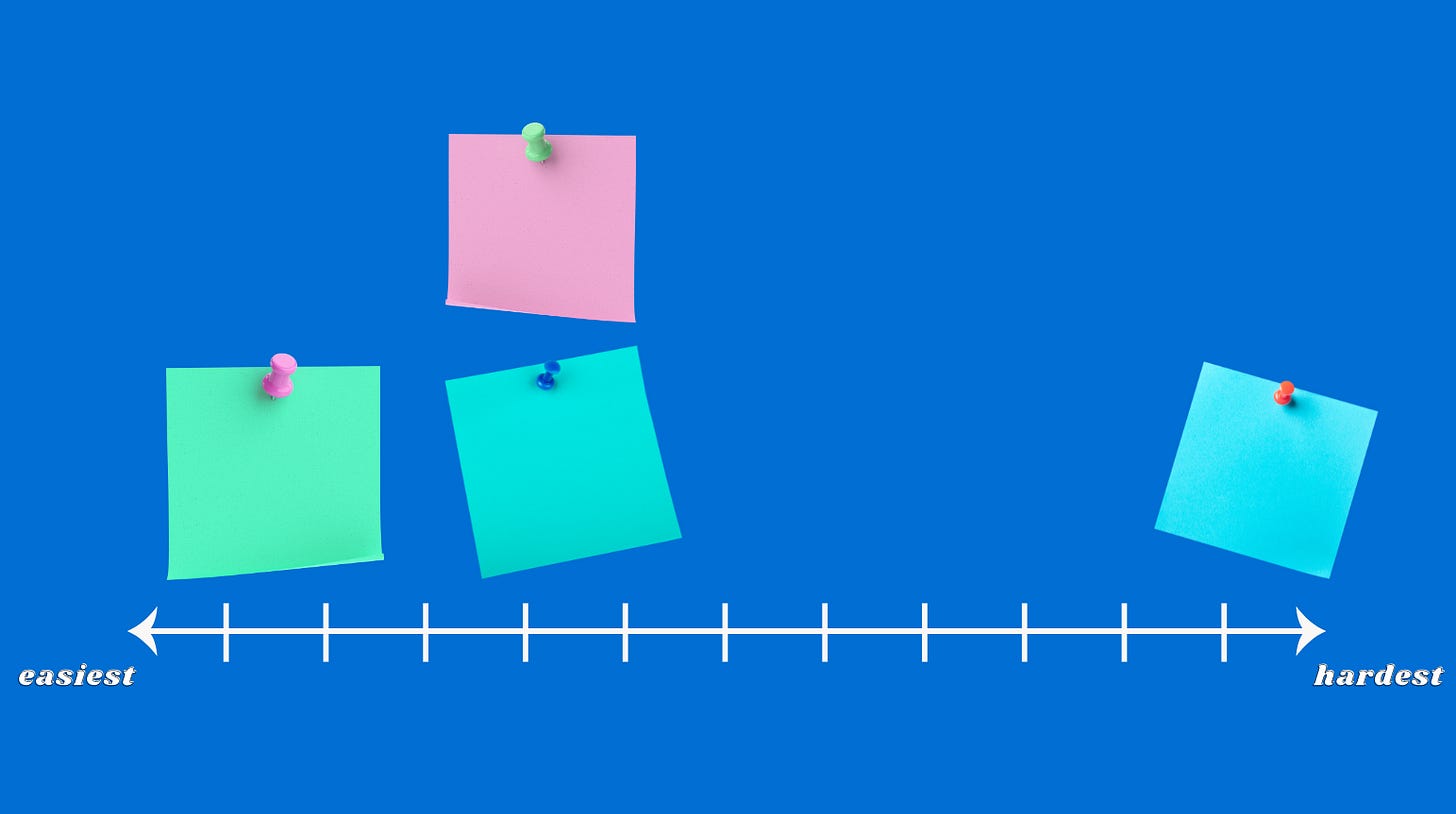

Put all of your tasks on separate post-it notes with a visual anchor on each end of a spectrum (easiest to hardest; most to least time consuming; most to least help needed, etc.)

Writing a to-do list together before you go somewhere (like the grocery store or the library), again with scaffolding so that you can help your child decide the sequence and what should be prioritized

Preparing for a task to end through reminders (i.e. “soon _____ will be finished”) and visuals. A useful tool for this type of preparation is a countdown clock (you can also use a digital timer, but sometimes that can increase a child’s anxiety about running out of time): here’s the one I typically use at work (see image above), but this one could also be fun since it’s magnetic—easy to attach to your fridge! Or, if you’d rather go for a throwback, hourglasses are actually very popular at school. They tend fall under the so soothing ASMR category for kids.

Are there any time management strategies I forgot to mention that you found helpful as a kid or that you use now? Drop them in the comments below!

Whitman, G., & Kelleher, I. (2023). Neuroteach: Brain science and the future of Education. Rowman & Littlefield.