Dearest Reader,

Welcome to the first newsletter of the summer focused on writing, specifically letter writing. No, not handwriting. Writing letters—you remember, those pieces of paper we used to get in the mail and they would come in envelopes. Yessss those letters.

Hopefully you had the chance to look over my most recent newsletter about stationery, in which I touched on how letter writing has been all but eradicated from most school curriculums. A skill once experienced in every day life has been replaced by technological advancements—in this context, email and texting.

Of course email, oh sorry e-mail1, originally stood for electronic mail aka electronic letters. Correspondence leaning informal in the recent decades has had its perks for sure, but the downside to me, as someone working in early childhood and elementary education, is the loss of a real life skill—don’t forget, most jobs these days involve answering emails, some for 8-10 hours a day.2 Considering letter writing is one of the most formulaic and routine writing forms with a historical significance across all ethnicities and nationalities, ignoring its significance and need for formal practice puts our kids at a great disadvantage.

Now before I get into ways you and your family can write more letters at home, I want to touch on five important skills embedded within written correspondence that will either enhance a child’s communication or fill the gaps that conversations lack:

Reciprocity

In typical development, humans begin to engage reciprocally with their caregivers around 3 months old through smiling, cooing, and making other vocalizations (example: blowing raspberries). This is the beginning of intentional communication. True reciprocity feels rhythmic and predictable, and it can provide comfort with or even admiration for another person. It’s the feeling of truly connecting with someone. Sending and receiving letters can serve as another medium for reciprocal communication.

Kids with language-based learning disabilities and other language disorders may have notable difficulty maintaining reciprocity within conversations3. This can look like becoming easily distracted and losing their train of thought or shifting their attention within a conversation, whether it’s looking around the room or changing topics. They may also impulsively speak out of turn or say something unrelated in the middle of a conversation that breaks the flow of reciprocity.

Conversely, in order to break the flow of reciprocity when writing letters, someone would have to actively decide they are not going to write back or delay responding for so long that it gets dropped all together. That takes much more forethought than a conversation, making the act of writing purposeful—remember, purposeful communication is always the goal.

Topic maintenance

Now, topic maintenance is an oft-mentioned social skill that feels pretty subjective as a clinician. How long do we really need to stay on just one topic? What if a personal anecdote feels relevant and takes the conversation in a new direction? Sometimes talking about one thing for too long unintentionally ruins the vibe of the interaction. In other instances, delving deeper into a topic alters relationships for the better.

Writing letters allows us to find the balance point of all these factors. We can respond with one or two sentences about a specific topic or idea across multiple letters while also focusing on others, and it doesn’t feel disingenuous or make the writer sound aloof. Planning and editing letters also helps us to self-monitor for conciseness and repetition of ideas.

Similarly to reciprocity, topic maintenance for neurodivergent individuals can be challenging for many reasons, whether it’s feeling more comfortable talking about a highly meaningful topic than what the other person would like to discuss or internal distractions taking their thought processes on a wild ride. However, when the material is written down it becomes permanent and static, acting as a visual support that they can look back at as many times as necessary.

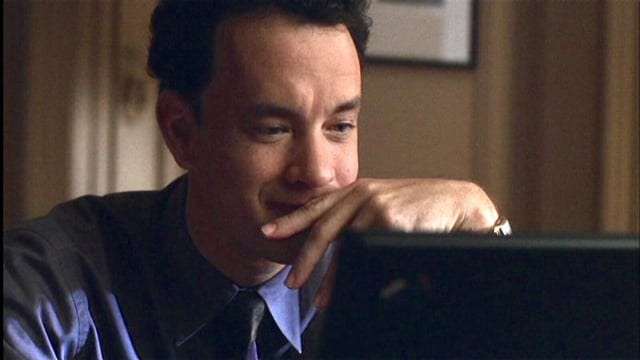

Shopgrl to NY152: “The odd thing about this form of communication is that you're more likely to talk about nothing than something. But I just want to say that all this nothing has meant more to me than so many somethings.”

Language functions and writing styles

We write letters for various purposes, including:

Recognizing and celebrating momentous occasions, like birthdays, anniversaries, and engagements

Saying thanks and sharing appreciation

Letting someone know we are thinking of them, especially when sending condolences

Building relationships and getting to know someone better

Informing someone of life updates or sharing new information

Attempting to convince or persuade

Wanting to gain information or learn more about someone’s experience

Many of these functions overlap with the academic writing that kids are tasked with in school—persuasive, informative, and narrative writing are all highlighted in the Common Core and lie within independent school curricula as well. The main difference here is formatting and organization; students being able to write across multiple forms increases their cognitive flexibility and written communication skills.

Kids with language-based learning disabilities and expressive language disorders will naturally communicate for fewer purposes, often leading to breakdowns, misunderstandings, and conflicts that they could struggle to problem solve.

For instance, these kids might easily direct the actions of others (“Give me that one”) or ask questions to obtain information about logistics (“What time is lunch?”), but experience difficulty sharing information about themselves (“I went to the baseball game yesterday”) and commenting on the here and now (“It’s really hot out today”). Pair this with “flat affect” like a monotone voice and neutral facial expressions, and the results are an unintentionally intense and off-putting persona.

Writing, on the other hand, allows the individual to plan out and tailor the exact reason for communicating, altering the language and “voice” to appropriately fit the context. This means that a person who has challenges persuading someone tactfully when they are speaking may be able to expertly convince people through their writing. It could also provide the opportunity for someone to convey their inner life and share stories, especially when communicating face-to-face is too hard or overwhelming.

Forming relationships

Another difference between letter writing and most other writing types is an underlying social motivation. We want to connect with someone we care about. We want to write something that they’re motivated to respond to and not just throw in the garbage.

Sustaining meaningful relationships and feeling part of a community should always be the primary focus. If you have a child with ADHD, Dyslexia, ASD, or any other language-based disability you know that they are more likely to have to participate in tutoring, academic camps, summer school, and individualized therapies over the summer while their friends can relax all day and just focus on summer reading. Letters are a way to keep their writing skills stable throughout the summer without having to sacrifice social time to tutoring throughout the week. It also helps kids remain connected to friends and family.

The importance of processing time

A positive aspect of the postal service’s slower pace is that a natural feeling of anticipation is built into the process of writing letters, which subconsciously can add excitement to the arrival of our mail or make it a fun surprise when we receive a letter unexpectedly (as long as it’s not a bill). It’s also helping kids to build object permanence, or the understanding that something can continue to exist even when out of sight or mind. I have mentioned object permanence across many different posts, but one aspect of it that I have not touched on in as much detail is the concept of someone’s feelings existing when that person is out of sight.

It’s why many people get sent into a tailspin with texting—are they thinking about me??? Do they still like me?? Do they want to see me again?? People have become so accustomed to quick responses that when someone takes longer to respond, it can be very confusing . On the other hand, a slower pace is the expectation for letters.

It’s also quite normal to be impatient waiting for letters to arrive, but a quick trip to the mailbox or going to the post office is a nice, regulating routine (plus you’re getting a little movement in, even if it’s just to the end of your driveway). For neurodivergent kids processing time is often essential, so the slower pacing of snail mail is advantageous and often regulating in comparison to FaceTime calls. Regardless of whether or not your child is actively writing letters, having them check the mail is a great afternoon routine especially on a warm summer evening stroll.

This abbreviation dates back to the 1970’s, which is crazy to me, because I only think of it in the context of Y2K when we started to shorten everything similarly

As much as we hate to admit how hard we have to work to get to inbox zero

Paul, Rhea, et al. Language Disorders. Mosby, 2025.